Blog:

The Seattle Interactive Conference: Jacob Caggiano’s big questions

In my first post on the Seattle Interactive Conference, I went over some locally developed tools designed to make information more relevant and insightful. Mobile apps like Trover, which allows geo-discovery through photos, and Evri, which organizes ~15,000 news feeds into a friendly iPad interface, are useful on an individual level. But my concern is:

How can they scale to community heights when it comes to breaking, spreading, and contextualizing important public information?

Technology scales best when community needs come first. Photo by Lisa Skube.

This is not an easy question. To help answer it, I needed to figure out how the mobile sausage is made. So at SIC, I tracked down John SanGiovanni, co-founder of and product design VP for the Zumobi mobile network. It would be wrong to call Zumobi an “ad network,” because while they do serve ads to mobile devices, they also design and build the apps on which the ads run. Right now its “co-publishing network” is being used by some of the biggest heavy hitters in the content world, with clients that range from MSNBC and The Week magazine, to Popular Science, Good Housekeeping, Parenting Magazine, and Motor Trend.

The good news is that SanGiovanni happily reported financial success on the journalism side of their business. He said their MSNBC app is “a whale” (very profitable) and both the advertisers and the publisher (MSNBC) are happy with the model they’ve set up. It’d be hard not to be, because Zumobi designs and builds the app absolutely free of charge to publishers whom they choose to work with. The company also helps with some of the ad sales, but as a co-publishing network, they expect the publisher to already have a drawer full of dedicated advertisers.

The not-so-good news is that Zumobi only works with top tier clients and doesn’t have plans to scale down their model to independent and hyperlocal publishers. SanGiovanni assured me he’s a big fan of Maple Leaf Life and cares about supporting grassroots journalism, but it’s just not in the cards for Zumobi right now. The company prefers to swim with bigger fish.

The reason why this is not-so-good news, rather than bad news completely, is that it means there are still entrepreneurial possibilities for co-publishing networks within the mobile hyperlocal space. SanGiovanni said that while Zumobi can boast a working paradigm, they’re not sure they’ve completely “cracked the code” and are still settling “the Wild Wild West” when it comes to this type of content model. Right now their biggest competitor is the Google acquired AdMob. Zumobi believes it has a leg up on AdMob, claiming to be the only ad network that lets an advertiser choose exactly in which app its ad appears, rather than limiting the advertiser to a single bundle and little control.

Hearing the “Wild Wild West” metaphor reminded me of similar analogy I heard during a panel from Geekwire’s Monica Guzman. She described the freshly chartered #SoLoMo (Social, Local, Mobile) space as a “land grab” to be first to own the territory. Guzman said that even big players like FourSquare have yet to demonstrate solid roots such as a profitable horizon and control of the market.

The race to settle the Next Frontier

Guzman followed up her “land grab” metaphor with a very excellent point: there’s a lot of talk about collaboration within the ecosystem, but secretly, everyone wants to build their own private roads and charge a toll. James Grimmelman, associate professor at New York Law School and part of its Institute for Information Law and Policy lays out the legal catfight in great detail with his indispensable piece, “Owning the stack.”

As the industry continues the battle and enacts agreements on borders and territory, it’s important that you and I understand the collateral damage that’s at stake for individuals and the community at large. There are a wide variety of intersecting issues to explore (privacy, security, affordability, accessibility, interoperability, obsolescence). One that needs better elaboration is:

Data Portability

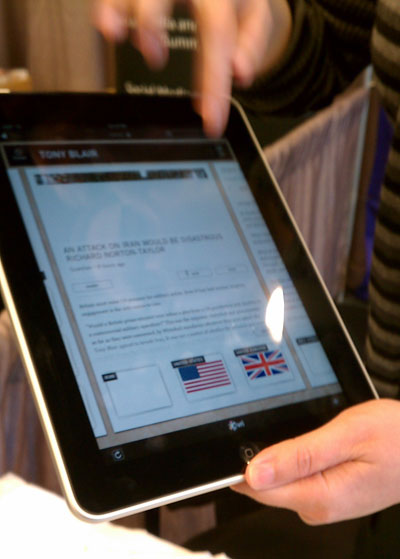

Test driving Evri at the SIC. Photo by Jacob Caggiano.

I popped the big question on data portability throughout the event and sincerely hope others bring it up when I’m not around to do so.

What are my options for getting data in and out of App X, and why are certain options unavailable when there are clear use cases to support them?

All developers think about data portability when they build software, and all consumers should think about it when evaluating and adding to their tool set. The silent ills caused by walled gardens are becoming more widely recognized – witness Google’s flaunting more flexible data options as they continue to develop their Google+ network. While representatives of Google and Facebook joined the Data Portability Project in 2008, the advocacy group’s chairman Steve Repetti has clearly not been satisfied. He recently threw down the gauntlet and demanded they settle things once and for all at a yet to be announced Data Portability Summit.

Let’s take a step back and show you why this issue is so important. How many of you have lost your phone but didn’t want to pay for Sprint’s backup system, causing all your contacts to instantly vanish? Technologically, it’s a piece of cake for device makers to build a function that exports a basic comma separated text file (.csv) of your contacts directly onto your hard drive without an internet connection. Feature-wise, it’s great for consumers because any computer in the world can read that .csv file, guaranteeing no choke points when you need to connect with your special someone.

This basic functionality is slowly coming along, but there are still many sticky points. Verizon customers get free cloud backup, but how easy is it for you to recover your contacts if you lose your Verizon phone and want to switch providers when you get a new one? You’re definitely out of luck if you want to load your contacts into a friend’s phone during the interim. Lost your phone the day before your trip to Europe? Too bad.

The point is, regardless whether a free cloud exists, it’s still a very opaque cloud (not to mention less private, secure, and accessible than a local backup file via USB). Regardless of company promises, nothing matches the peace of mind of having a human readable file on your very own hard drive that you can transfer to any device without an internet connection.

This is just one example. Lack of data portability comes in many forms, and the barriers are put in place by a cross section of industry players. On Facebook there’s been a long, drawn out battle to have one click exporting, with the company issuing a series of legal threats against developers who make third party applications that do things like make it easy to download photos. (Google and Facebook also have their own personal battles on this issue.)

Buttons and picks: The Tableau table offerings at SIC. Photo by Jacob Caggiano.

As it turns out, the purported 5th of November attack rumored from Anonymous didn’t happen, but those who tried to safeguard their personal data had to waste a good deal of time to discover a partial workaround that requires all your data to go through a Google account. What’s going to happen when a better system comes along that is more respectful of privacy and ownership (i.e. Diaspora*)? Will social networking innovations be able to succeed if people can’t easily migrate their delicate relationships over to a new home?

This is clearly a longer conversation for another time, so in the context of the Seattle Interactive Conference, I asked Shannon Carter, design director for Zumobi, about data portability during the Q&A of her presentation on mobile UX design. She outlined a general strategy of keeping as much data within apps as possible, but allowing sharing via Facebook and Twitter.

I’m not writing to pick on Shannon or Zumobi for following the big player trends away from data portability. That said, here’s the bottom line: The ability to mash up public information and protect private information will be directly affected by the business decisions made in the coming years. These business decisions will come from a general industry consensus, which is leaning in the direction Shannon’s heading – building apps that share with popular proprietary social networks, but keeping the data sealed shut within the app.

Achieving true data portability is a challenging fight when we have to rely on our imaginations to see how much better the world could be in a future with universal open standards. So let’s look at the past. Imagine what the world would be like today if Tim Berners Lee chose to patent HTML, and thus the World Wide Web. We’d probably be living in a twilight universe of kitschy AOL style portals where the highest bidding sponsor gets to load their mediocre content on your home screen. Instead, for now at least, we can watch social revolutions unfold through real-time, firsthand experiences, shared directly from the person witnessing them.

What are your thoughts on data portability and the vision of an Open Web? How can we build financial rewards to innovative companies who make products that play nice with user controlled data?

About Jacob

Jacob Caggiano writes about his “healthy obsession” with communicating online, and more, at futuresoup.com. He has worked with innovative groups like the Knight-Mozilla Partnership, Journalism that Matters, and the Washington News Council. He helped create the Seattle Journalism Commons, and co-organized the 2011 Open Video Conference in New York City.

Weigh In: Remember to refresh often to see latest comments!

0 comments so far.